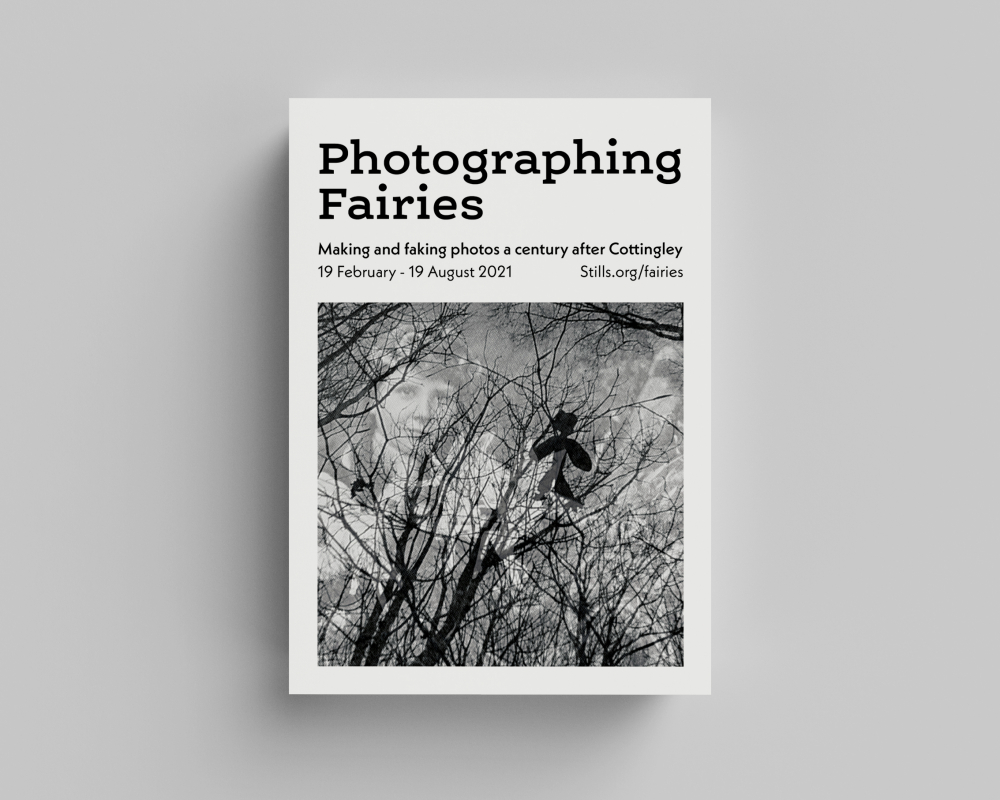

Exhibitions

Photographing Fairies

Part One

Fairies Photographed

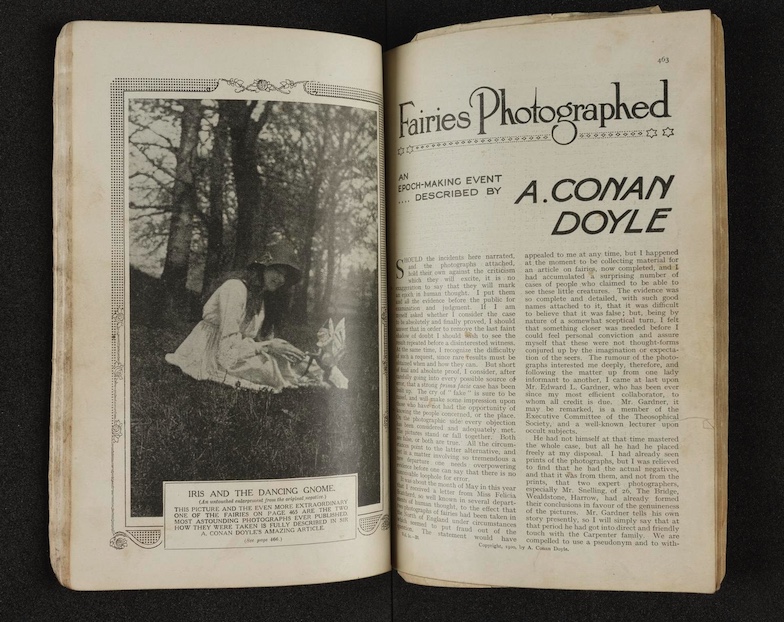

The Cottingley Fairy Photographs are five notorious pictures taken just over a century ago in the village of Cottingley, Yorkshire. They were made by two cousins, Elsie Wright and Frances Griffiths, but they were made infamous by Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, the Edinburgh-born creator of Sherlock Holmes.

The Strand Magazine, December 1920

Science Museum Group © The Board of Trustees of the Science Museum, London

The recognition of their existence will jolt the material twentieth-century mind out of its heavy ruts in the mud, and will make it admit that there is a glamour and a mystery to life.

Arthur Conan Doyle, 1920

The photographs in the Strand article had been taken in the summer of 1917, when nine-year-old Frances and her sixteen-year-old cousin Elsie often played around a wooded stream known as Cottingley beck. One sunny day in July, the two girls borrowed a camera from Elsie’s father, and returned with a remarkable photo of Frances with a group of dancing fairies. A while later, they produced another one, of Elsie with a dancing goblin.

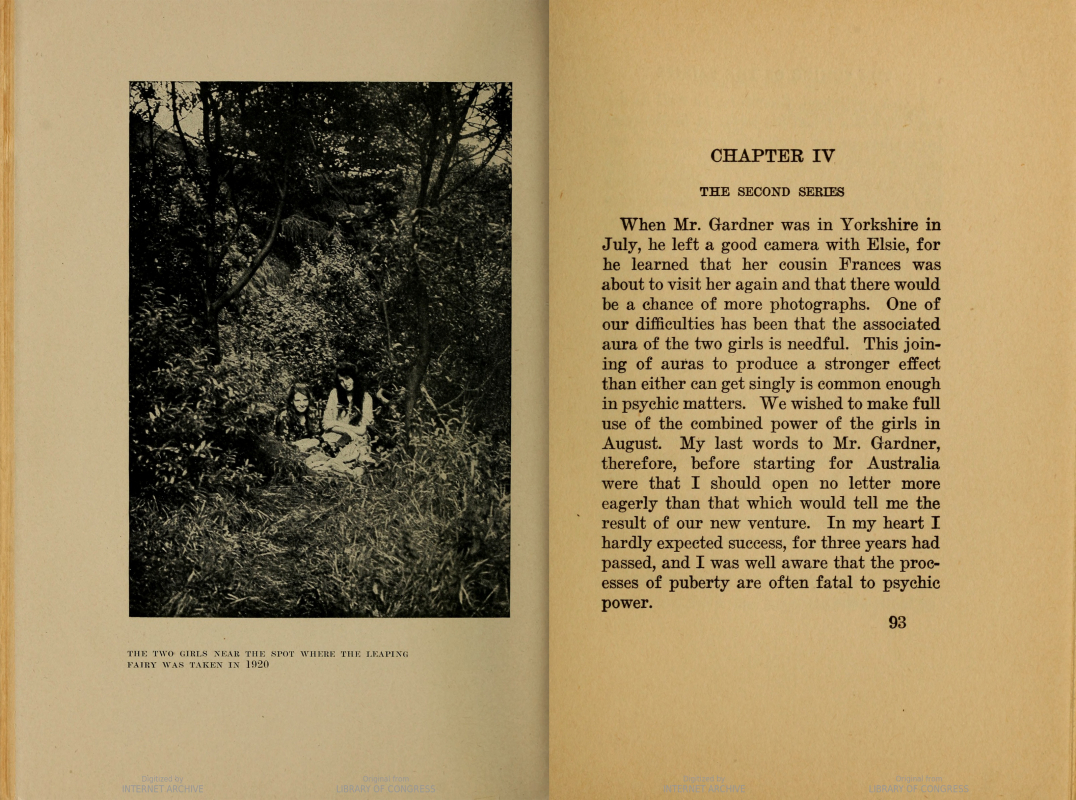

By 1920, the two photographs reached Edward Gardner, a Theosophist with a committed belief in fairies and other elemental beings. He took them to Arthur Conan Doyle, who famously believed in Spirit Photography. Keen to verify the sightings, Gardner visited Cottingley in July 1920, taking new cameras for the girls, and encouraging them to take more pictures. The girls obliged with three new photographs.

These two Yorkshire lasses had created the original viral selfies – photos which convinced many people of the existence of supernatural life, but also sparked fierce debates about the truth of photography, and the agency, ability and innocence of girls. Elsie and Frances kept their secret until 1983, when they finally revealed how they’d made the photographs. They are now symbolic of the girls’ wit, imagination and friendship.

To discover more about the Cottingley Fairy Photographs and the artists shown below, download the exhibition booklet here.

Which is the harder of belief, the faking of a photograph or the objective existence of winged beings eighteen inches high?

Maurice Hewlett, John O’London’s Weekly, 1921

That first picture has echoed round the world ever since as a perfect expression of innocent childhood and a belief in fairies.

Geoffrey Crawley, British Journal of Photography, 1985

The first time I saw the little man – he was about eighteen inches high – he was walking purposefully down the bank… I wasn’t unduly surprised – the beck was a wonderful place and I wouldn’t have been surprised at anything that happened there.

Frances Griffiths, Reflections on the Cottingley Fairies, 2009

Elsie and the Gnome, September 1917. © National Science & Media Museum/SSPL

They may have their shadows and trials as we have, but at least there is a great gladness manifest in this demonstration of their life.

Arthur Conan Doyle, The Strand, 1920

Frances and the Leaping Fairy, August 1920. © National Science & Media Museum/SSPL

They are probably the most interesting photographs ever obtained in the world, and the negatives were submitted to the greatest photographic experts who found no flaw in them.

East African Standard, 1929

Fairy Offering Posy of Hare-Bells to Elsie, August 1920. © National Science & Media Museum/SSPL

…the “bower” one was utterly beyond any possibility of faking!

Edward Gardner, 1920

Fairies and their Sun-bath or Bower, August 1920. © National Science & Media Museum/SSPL

It may be taken for granted that the stories about the fairies when first published were received with a degree of scepticism which was only to be expected… Still, there was the camera, which, we are told, cannot lie.

Shipley Times and Express, 1921

They ought to have supplied Elsie with a butterfly net instead of a camera.

Truth Magazine, 1922

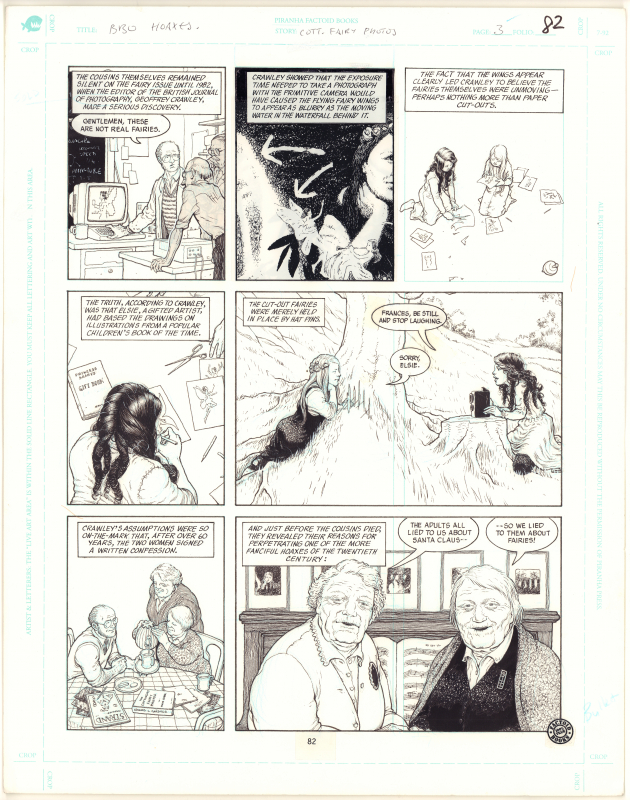

In the early 1980s, Elsie explained how the pictures had been made: she had cut out drawings of fairies and stuck them in the earth with hat pins. This reignited interest, including books and films that confirmed the legendary status of the Cottingley Fairy Photographs.

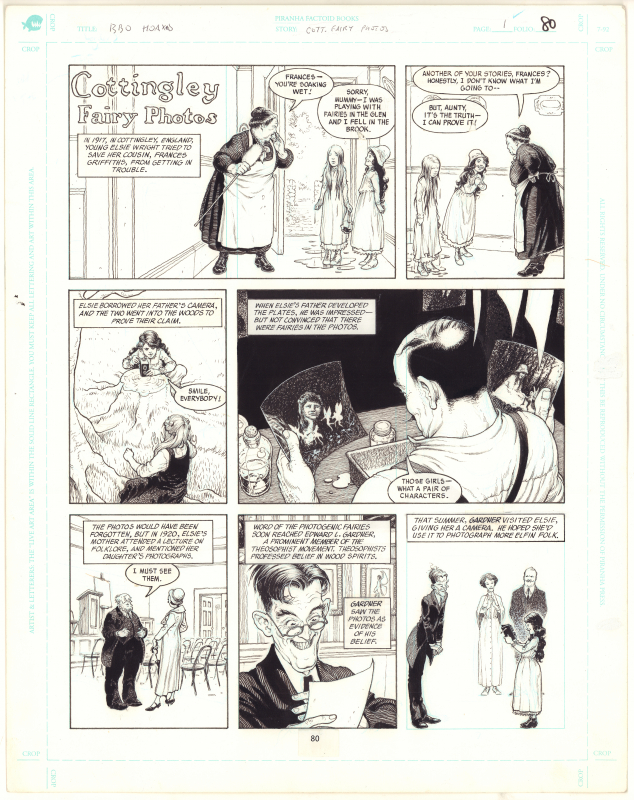

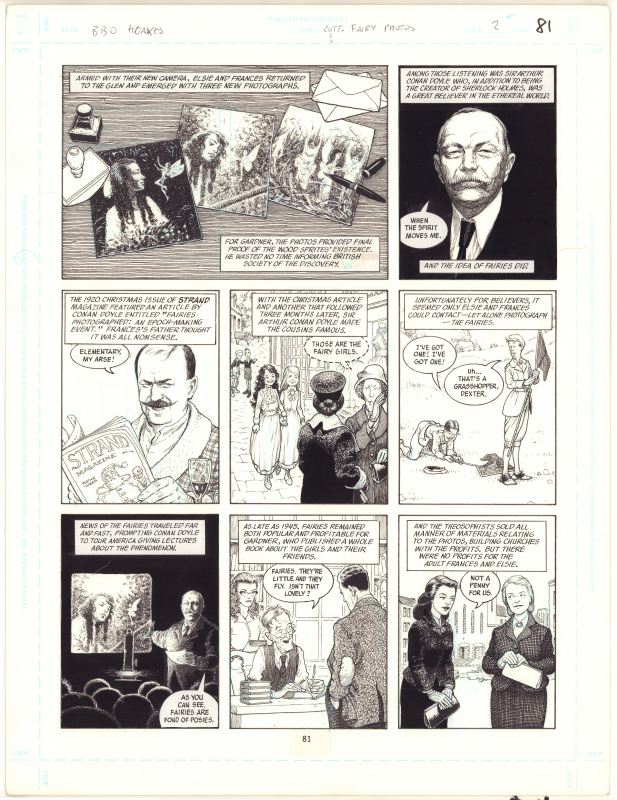

In 1996, Frank Quitely illustrated the story in a 3-page comic for The Big Book of Hoaxes. Quitely’s original artwork shows the blue pencil lines used in comic art. Unlike fairies, which apparently registered on photographic plates, the blue sketch lines disappeared on the orthochromatic film used in publishing.

Part Two

The Case for Spirit Photography

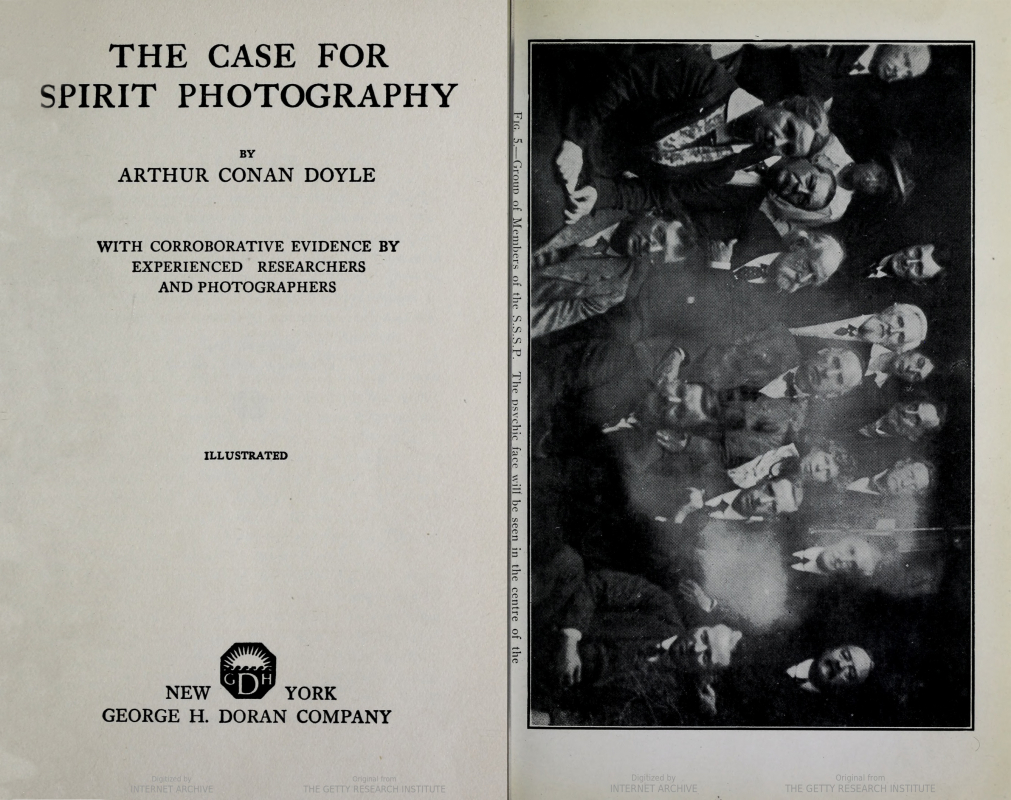

Arthur Conan Doyle embraced the Fairy Photographs as evidence of life and energy beyond normal human perception. His long-held commitment to Spiritualism had intensified after his son’s death in 1918, and he turned to Spirit Photography in hope of reunion. To Doyle, fairies and photographs were both potential tools of necromancy: contact with the dead.

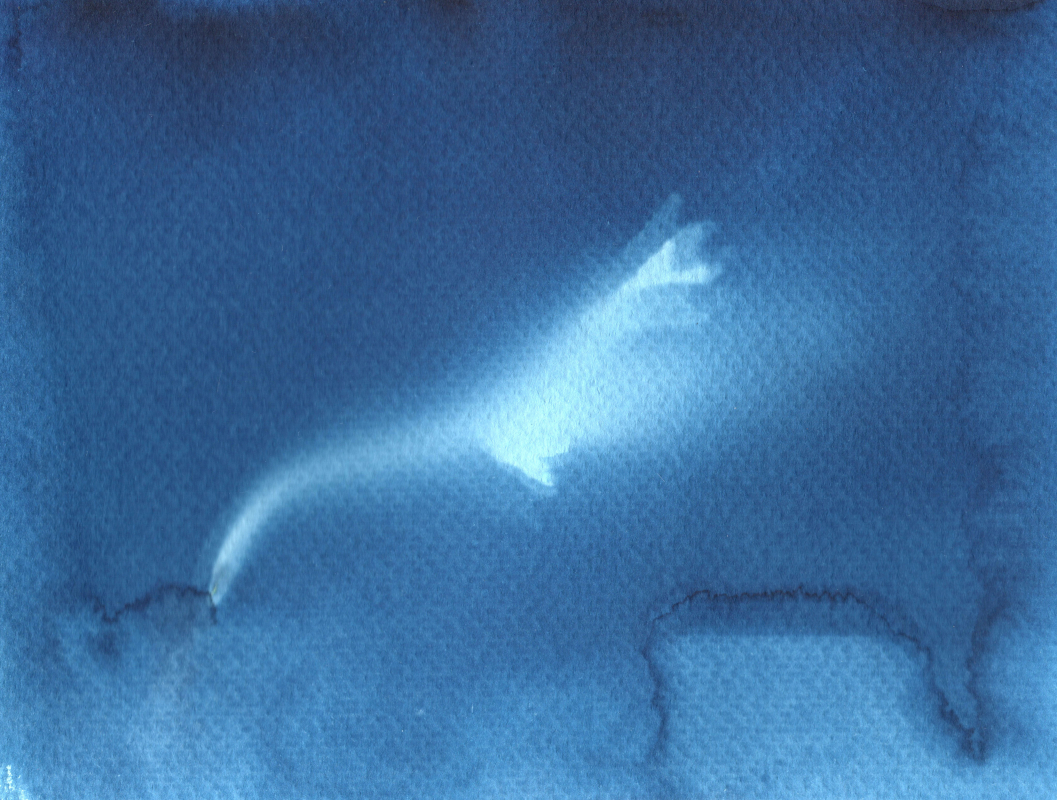

A century later, the supernatural promise of film, paper or pixels continues to enchant photographers. In 2020, Morwenna Kearsley summoned a ghostly presence into a bell jar during a mysterious darkroom ritual. And during the Photographing Fairies project, mysterious cyanotypes registered the auras of objects nearby…

In this book, Doyle passionately defended the Spirit Photographer William Hope against claims of fraud.

His remarkable work has brought consolation to the afflicted, and conviction to many.

Arthur Conan Doyle, 1922

The Case for Spirit Photography, Arthur Conan Doyle, first published 1922

The War brought about a great wave of feeling in support of spiritualism, and not even the most hard-headed sceptic could refuse his sympathy to the mood which sought relief from sorrow in the hope of a possibility of communication with the other world.

The Scotsman, 1922

I hold the negative up to the light and a bolt of electricity runs through me… Whose is this body, floating in the deep, dark shadows of the negative?

Morwenna Kearsley, Sundae for Lee Miller, 2020

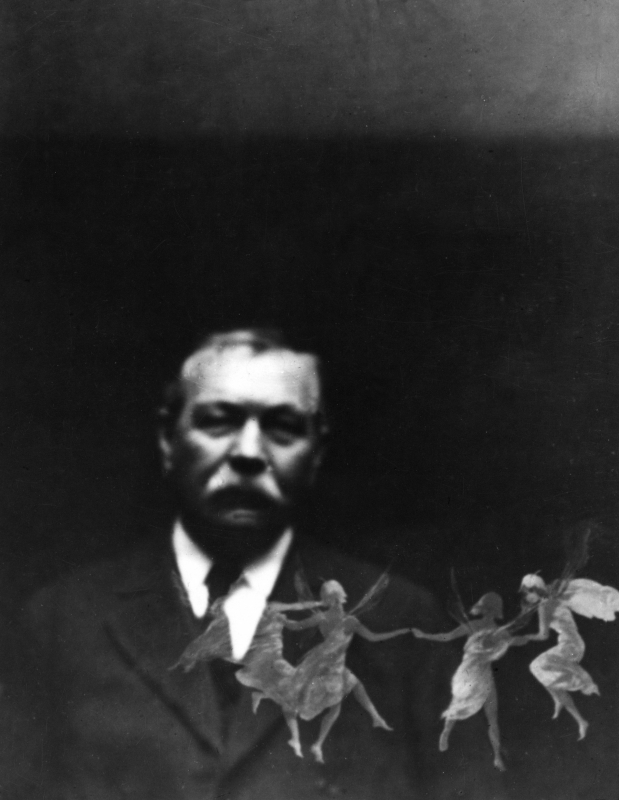

William Marriott was a determined debunker of Spiritualism. He made this double exposure portrait of Doyle at a public lecture to demonstrate the fraudulent methods of Spirit Photographers.

Sir Arthur Conan Doyle with Fairies, William Marriott, 1921. © Harry Price/Mary Evans

Extreme incredulity is even more disastrous than extreme credulity.

Arthur Conan Doyle, 1922

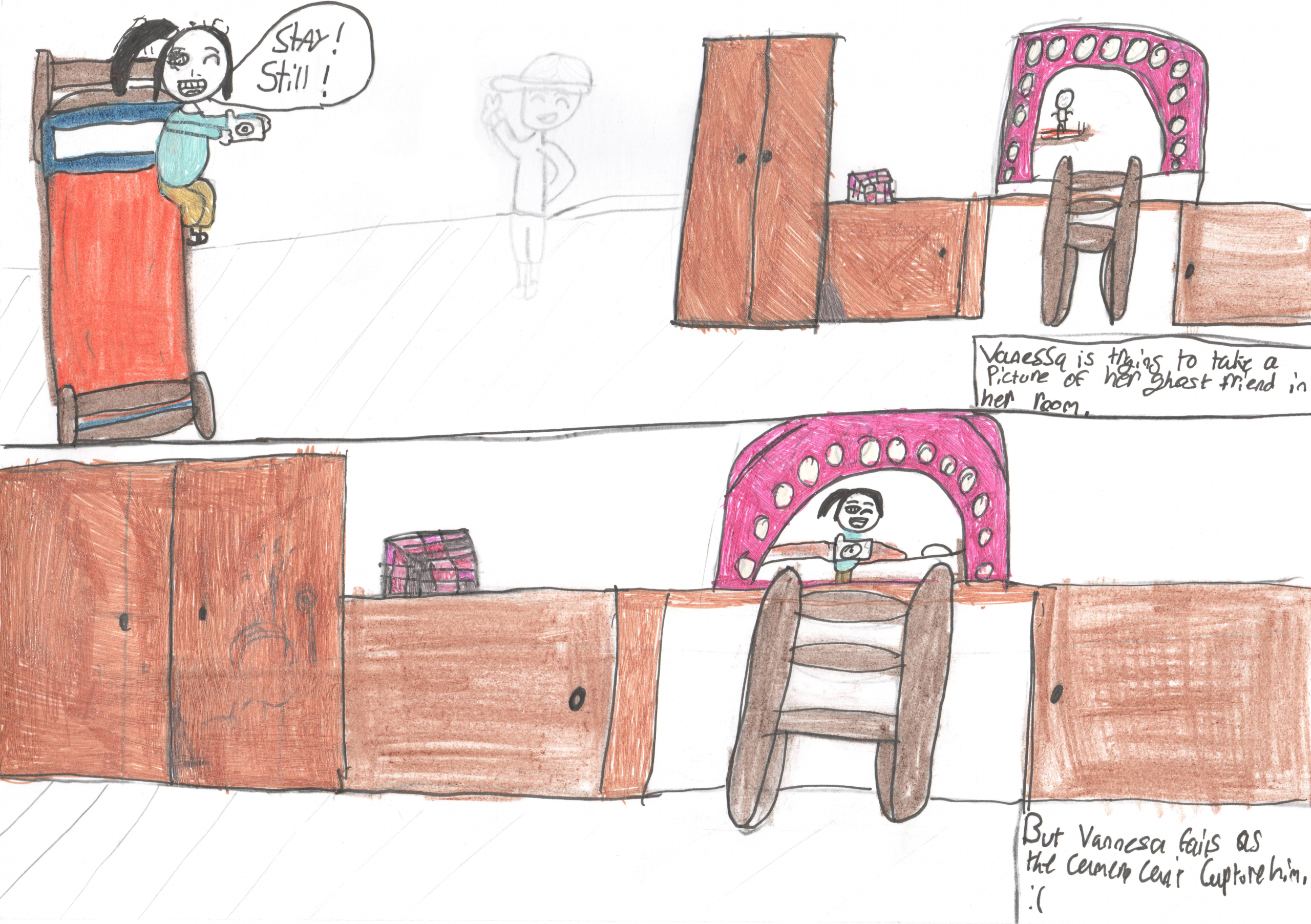

“Stay! Still!” Vanessa is trying to take a picture of her ghost friend in her room. But Vanessa fails as the camera can’t capture him 🙁

Capturing Ghosts, Chloe, 2020

Part Three

The Coming of the Fairies

In truth, Elsie and Frances had no need of assistance from ectoplasmic spirits, telepathy or even photographic trickery. The fairies were real figments of their imagination, drawn on paper and cut out by hand.

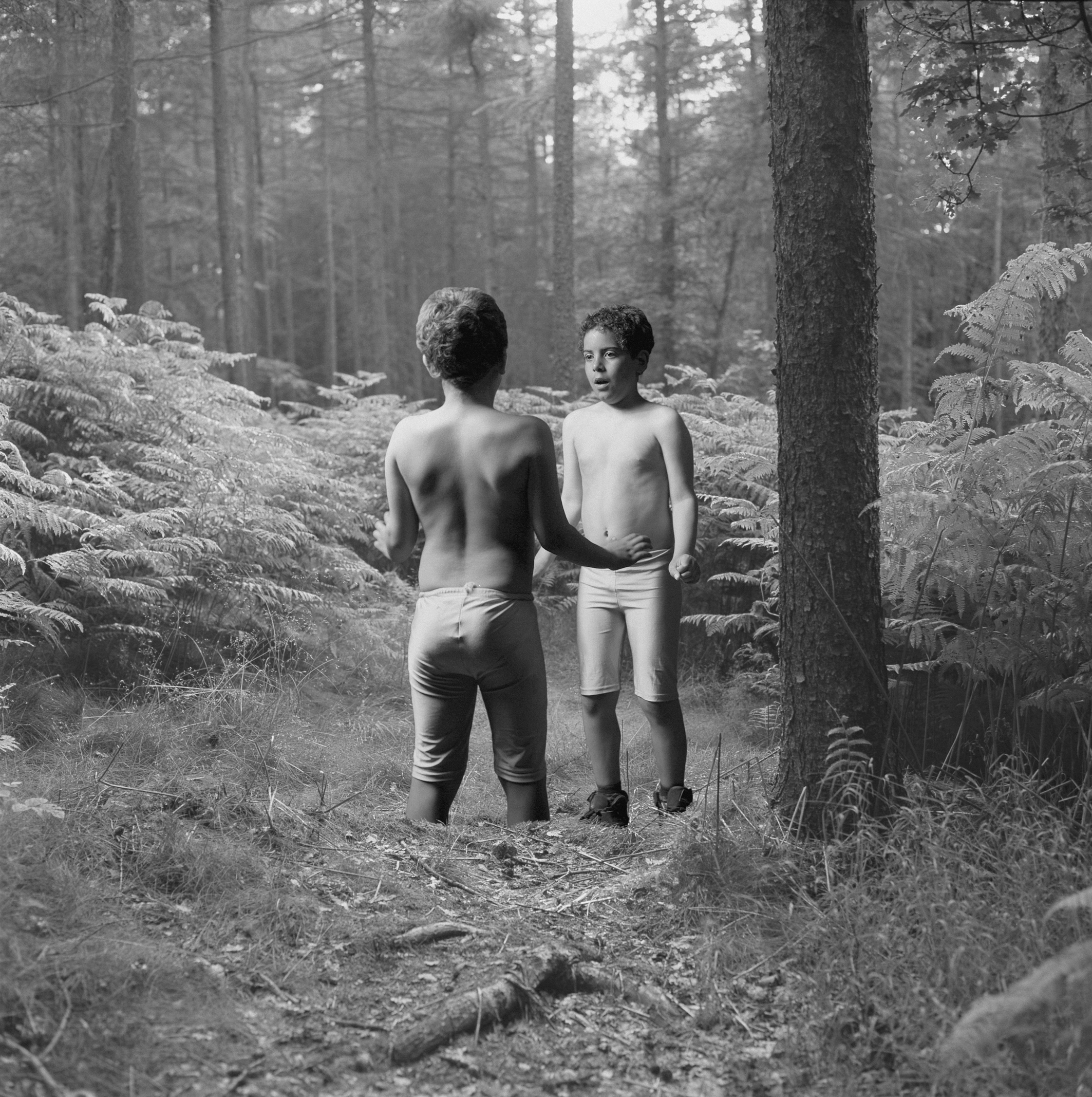

Doyle saw how the curious intensity of young female friendship makes girls even stronger in pairs – through what he called the ‘joining of auras’. In the 1990s, Wendy McMurdo developed this theme of doubling and reflecting, using digital cut-and-paste to reveal the reality of imagination. How might Elsie and Frances have used photoshop if they were young today?

In this book, Doyle explained his theories of fairy life, and the mediumistic power of girls.

The Coming of the Fairies, Arthur Conan Doyle, 1922

Two collaborators – minxes shall we call them? – have deceived “the very elect”. More power to their scissors! we say.

Edward Clodd, Occultism, 1921

I try to literally force an image into what I think is an emotional truth.

McMurdo, 2002

There are fairies at the bottom of our garden!

You cannot think how beautiful they are …

Rose Fyleman, Fairies and Chimneys, 1918

The reaction to Elsie and Frances’s photographs foreshadowed 21st century anxieties around authenticity, fake news, deep fakes, image manipulation and the unpredictable power of certain images to fascinate, reproduce and spread virally.

The Cottingley Fairy Photographs have remained enchanting and provocative images. They provoke our desire to believe, as well as destructive urges to debunk and denounce. They have the ambiguous clarity of a good meme – their subject is easily grasped, but their meaning is up for endless debate.

It was great fun while it lasted.

Yorkshire Post and Leeds Intelligencer, 1944

Download the exhibition guide

Discover more about the artworks on display. Includes curator’s essay, more information about the project, and reflections on fairies and photography.

Make your own fairy photographs

Complete the attached form and we will send you a fairy template to make your own photographs.

Or download a digital version here.

Share your fairy photographs

Visit our social media to see how people have summoned fairies into their photographs, and share your own.

Acknowledgements

During lockdown in 2020, artist Morwenna Kearsley worked with young people aged 12–14 who meet regularly through Edinburgh Young Carers and Multi-cultural Family Base. Download the exhibition booklet to learn more about the project and see more of their work.

With thanks to all contributing artists:

Aïda

Aseel

Charlie

Chloe

Frank Quitely

Hannah Kearns

Jayda Browne

Kelly Dunnett

Morwenna Kearsley

Nabia

Nerea

Shahad

Skye

Wendy McMurdo

Music by David F. Maxwell

Videos edited by Morwenna Kearsley

Illustrations by Theresa Thomson Malaney with technical assistance from Miyram Lacey

Curated by Alice Sage as part of a AHRC-funded PhD investigating fairies and fantasies in interwar childhood.

Particular thanks to:

Emma Black & Claire Cochrane, Creative Learning Managers

Evan Thomas, Technical Manager

This project has been supported by the Ragdoll Foundation and the CHASE Feminist Network.