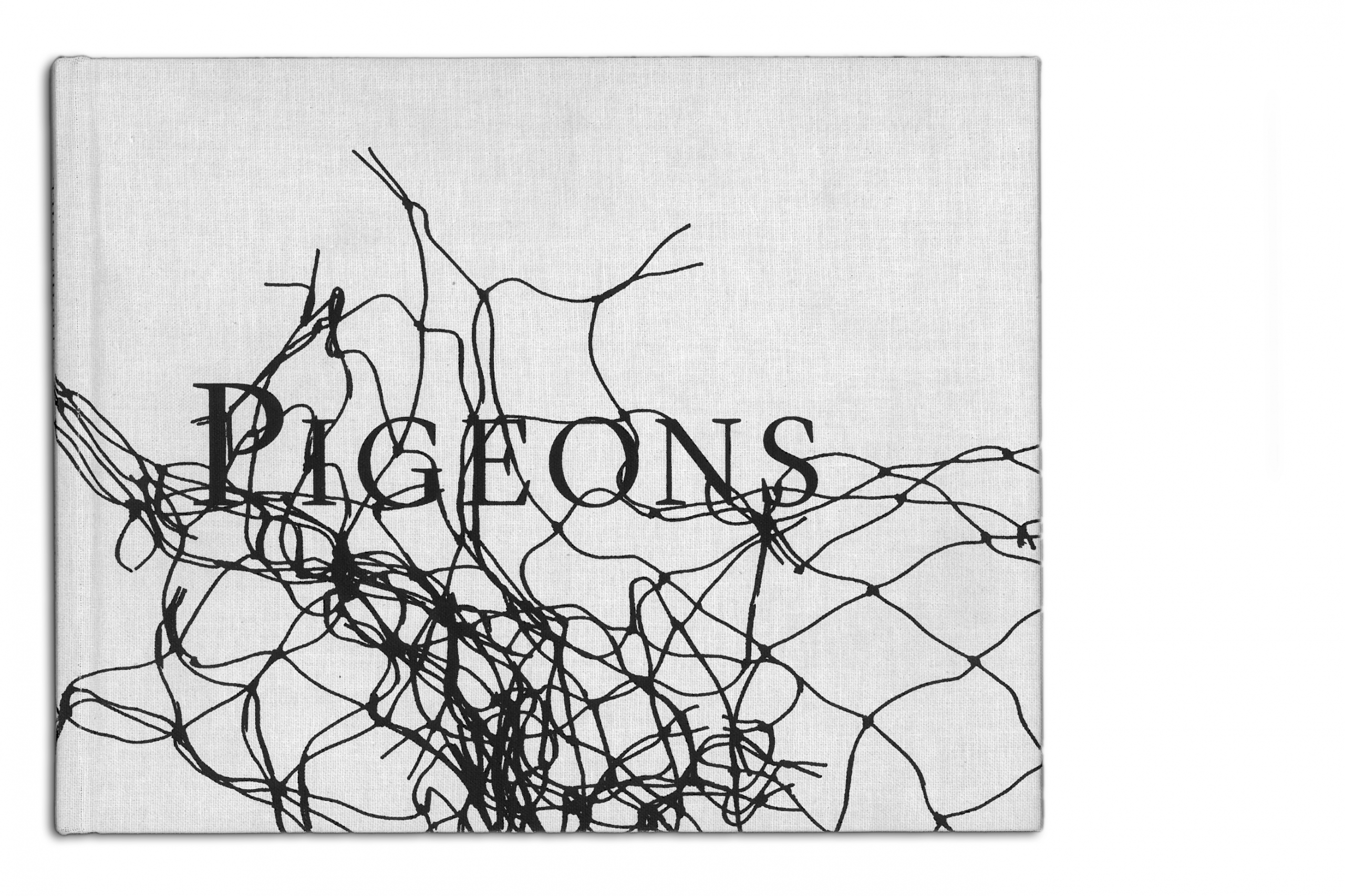

Stephen Gills photographs are devoid of sentiment or affectation rather than showing the pigeon in our world, they take us into theirs. The lens noses in under bridges, squeezes through cracks and scopes out crannies. These are images that bestow on the despised flying rats that oft-trumpeted but seldom realised attribution: their dignity: here are pigeons making their lives in a natural landscape, for, whatever else humans may be, we are animals too, and as such our buildings are analogous to the earthworks of termites, and our bridges to the dams of beavers. Its this inversion of the anthropocentric view that makes Gills images so compelling that, and another revelation; for, fluffed-up and blinking, in the dust and the grime and the rust and rime, we see those mythical beings: the young pigeons. I suspect its because we’ve entered this otherworldly realm that we find these juveniles to be arousing not of pity, but a grudging respect far from being scroungers, or undeserving poor, these doughty birds survive and even thrive, despite barbs and more barbs of outrageous human fortune. They are, like the urban foxes, the economic migrants of the animal world: forced into the cities to scratch a living as best they may, and before we condemn them we would do well to ask ourselves this question: would we do as well were the tables to be turned?

Will Self